Tamegroute Ceramics: A Brief History

Nearly 400 years ago, seven pottery families moved to Tamegroute, a small town on the edge of the Sahara Desert in modern-day Morocco. Centuries later, their direct descendants continue to produce distinctive green pottery using the same exact methods and materials.

Tamegroute to Timbuktu

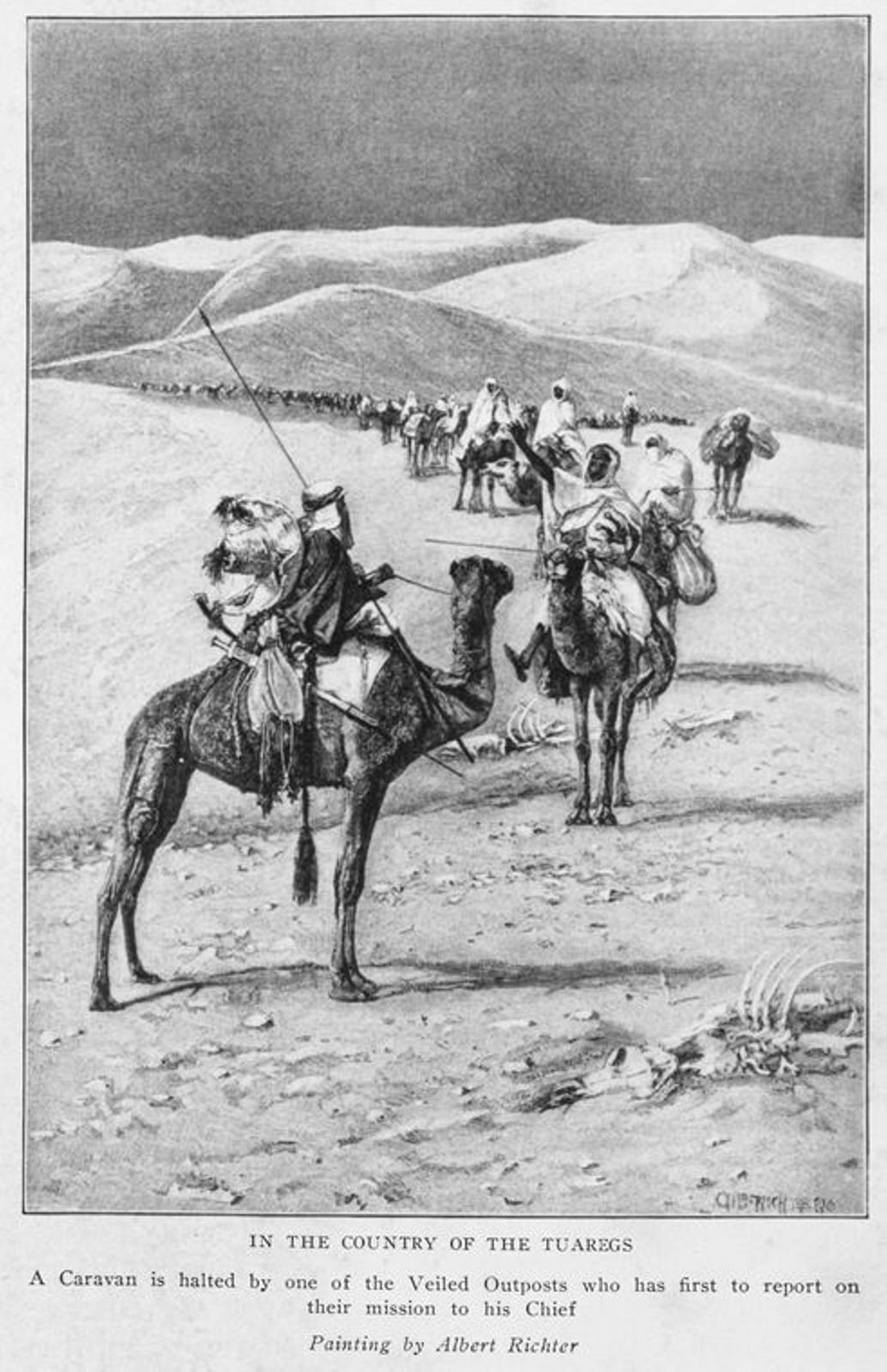

52 DAYS TO TIMBUKTU: the words (in French and Arabic) adorn the top of an illustrated directional sign featuring an indigenous Tuareg man wearing a signature blue turban, while a caravan of camels and date palms dot the background. This two-month trek serves as the subject for a mural found in several locations throughout Tamegroute.

The sign’s prevalence makes perfect sense given the history and location of the village. The word “Tamegroute” comes from the Amazigh term meaning “last visited stop,” or “last place before the desert,” an apt descriptor for the final rest-stop oasis before the hot sandy abyss of the Sahara Desert. Thus, the history of trans-Saharan trade is intrinsically linked to the history of Tamegroute, and by extension, to the history of Tamegroute pottery.

For the sake of this article, I’ll use the endonym Amazigh (plural Imazighen) when referring to the indigenous people of North Africa who predate Arab migration to the Maghreb. The Imazighen are composed of many distinct ethnic groups, but the most prevalent group in Tamegroute is the Tuareg.

-

An important word to clarify from the onset is the term “Berber.” It derives from the Arabic word “barbar” meaning barbarian. This nomenclature largely fell out of favor by the late Middle Ages but was revived in the 19th century by French colonialists bent on sowing division and maintaining control over local populations. I can’t believe I never made this connection before because, in retrospect, it is so obviously pejorative.

A Golden Age

We often think of the Middle Ages as a long, bleak period of isolation and ignorance. In reality, globalism flourished during the so-called “dark ages,” and that fact is ever-apparent in medieval Africa. From the 7th century onward, vibrant networks of trans-Saharan trade routes linked the Mediterranean world to the sub-Saharan Sahel. Just like Asia and the Silk Road, medieval Africa relied heavily on the exchange of goods such as gold, salt and ivory, as well as associated transit and customs fees along these trade routes to enrich its empires.

By the 8th and 9th centuries, a new religion called Islam was spreading rapidly. So was Europe’s zealous pursuit of gold central to the manufacture of precious goods and mint coinage. Arab merchants operating in southern Morocco bankrolled trade caravans to cross the Sahara and bring back the precious metal, converting indigenous Amazigh guides to Islam along the way. It is estimated that at the trade's peak, as much as two-thirds of the gold circulating around the medieval Mediterranean originated in West Africa. This upsurge of economic and cultural exchange enabled previously agricultural societies like the Mali (1235-1670) and Songhai (1430-1591) to usher in a literal golden age for the empires of West Africa.

Trade also opened the floodgates for travelers and scholars from Africa to move around the world like old-timey travel influencers. My favorite anecdote from this era is about the ruler of the Mali Kingdom, Mansa Musa, who basically invented “billionaire mindset.” After converting to Islam in the 1320s, Mansa Musa traveled to Mecca for hajj with a crew of thousands, draped in Persian silks and a hoard of camels carrying thousands of pounds of pure gold. He spent so lavishly on this trip that he actually destabilized the Egyptian economy so badly it took 12 years to recover from the recession and inflation that Musa wrought. An absolute legend! Musa’s ostentatious displays of wealth and subsequent lore surrounding Mr. Moneybags tantalized the European imagination and fueled rumors of a city made of gold hidden in the heart of Africa.

The Catalan Atlas

The Catalan Atlas, an illustrated map from 1375 made by Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques of Majorca, is a great example of medieval globalism. One of the map’s six panels depicts caravan routes between North Africa and the Niger River (Sheet 6, National Library of France, Paris) including an illustration of aforementioned baller Mansa Musa holding a gold coin and scepter and wearing a golden crown next to a Tureng trader.

Location, Location, Location!

Meanwhile, in what is now called Morocco, trans-Saharan trade fueled the rise of the Saadian Empire (1554-1659); and at its peak, the sultanate’s dominion reached as far as the Niger River in the Sahel. By the latter half of the 16th century, the Drâa-Taghaza-Timbuktu passage became a preferred trade route for caravans crossing the Sahara, which ushered in a new era of economic and social prosperity for villages sitting on prime real estate in the Draa River Valley.

Tamegroute, aka “the last stop before the desert,” was one such outpost. Think of it as a medieval service plaza and last chance to fuel up (in this case, feed the camels) before hitting the open road. Tamegroute became a sort of a desert-adjacent melting pot of African and Arab-Muslim culture as formerly nomadic populations of Imazighen, Arabs, Jews and descendants of slaves gradually began to settle the region.

If you’re like me, a 52-day schlep across a sand ocean to reach Timbuktu sounds impossible and bad. So to compound that, I’m gonna hit you with some desert facts:

The Sahara is the world’s largest hot desert, covering over three million square miles, about 8% of earth’s total area!

It spans 11 countries.

Saharan sand dunes can reach heights of up to 600 feet.

On average it receives less than one inch of rainfall a year.

Humans are resilient and find ways to adapt, survive and thrive in even the harshest environments. Tamegroute is a fine example of using location to one's advantage, because material goods weren’t the only things exchanged across the desert. One of my biggest takeaways from the trip was appreciating how trans-Saharan trade routes doubled as a sort of medieval information highway, transporting ideas and news alongside gold and salt.

A library at the edge of the desert

A lasting monument to the robust trans-Saharan knowledge network is the hidden gem of Tamegroute– the Zawiya Naciria. This 16th century center of Islamic learning still operates to this day. Its library contains a treasure trove of more than 4,000 works on quaranic studies, math, science, philosophy and medicine. The oldest book is more than 1,000 years old and is written on gazelle skin. I asked my guide why the other books were produced on paper and this very serious man cracked a smile and said, “Because that is too many gazelles.”

You are not allowed to take photos inside the zawiya but don’t worry, I took notes. The library was founded in 1575 by Abou Hafs Omar Ben Ahmed Alansari, a scholar whose family had settled in Tamegroute.

In the 1640s, well-known scholar and doctor Sidi Mohamed Bin Nasir took charge of the zawiya intending to offer new opportunities to residents of the Draa valley through education. He founded the Nasiriyya Brotherhood, one of the most influential and, at the time, one of the largest Sufi orders in the Islamic world. He transformed the zawiya into a center of learning where as many as 1,400 students could live and study for free.

Around this time, Bin Nasir and members of the Nasiriyaa brotherhood enlisted scholars and artisans to move to the village in an effort to bolster the reputation and economy of the town. So they called up their artsy friends from Fes and invited them to relocate to the village, probably under the guise of a “really cool creative opportunity.” This marks the beginning of Tamegroute’s famous pottery industry.

The seven pottery families who moved to Tamegroute nearly 400 years ago faced the challenge of creating an artistic identity for this nascent town on the edge of the desert. The artists deliberately and collectively chose to emulate the green pottery of Fes, and to this day, their direct descendants continue to produce distinctive green Tamegroute pottery using the same methods and materials their ancestors employed centuries ago. I can’t help but wonder what those original artists would think if they knew that the tradition they set into motion has been so faithfully and lovingly fulfilled. Some art never goes out of style.

In the case of Tamegroute, the pottery is evergreen.